COVER STORY: Grief, Grit & Grace

Blacksburg, Va.—It’s an unusually mild winter day, yet no one at Virginia Tech’s College of Engineering seems keen to play hooky. Students drift in and out of Norris Hall, testing biomechanical robots or concocting stronger-than-steel new materials from glass fibers and resin. Over at the Ware Lab, senior design-project teams are scrambling to finish off-road and formula racecars in time to compete in national contests. Meanwhile, every lounge and nook overflows with Hokies huddled over laptops.

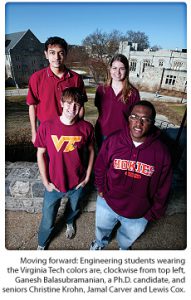

A year after the deadliest mass shooting in U.S. history visited horror and grief on this bucolic campus, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University’s largest college has recovered much of its bounce. Engineering research and funding, as well as admissions, remain robust. Strong campus spirit is widely evident in car decals and T-shirts in the school’s orange and maroon colors. Engineering students have lobbied the legislature on gun control and landed defense-research prizes. One attended the State of the Union address as the First Lady’s guest. And when the Engineering Science and Mechanics faculty began the sad task of trying to replace a murdered colleague, they drew an abundance of stellar applicants.

Except for the semicircle of stone memorials standing sentry over the vast Drillfield—honoring 32 victims, 14 of them engineering students and professors—reminders of the fatal morning of April 16, 2007 are mostly small and discreetly placed: a “We Shall Prevail” quilt in the student union, a student-built race car in the Ware Lab lobby with the words “In Memory” and names of victims on the seat, and a glassed-in bulletin board in Norris Hall containing a pastel portrait and obituaries of three slain professors.

But research displays, not plaques, dominate the cement-block corridors of Norris Hall, where a mentally ill English major named Seung-Hui Cho turned the engineering school’s central building into a bloody crime scene before training his gun on himself. And though a discerning eye might note the push-bars that have replaced the door handles so handily chained by the gunman to trap fellow students, the school has resisted installing fortress-like metal detectors. This in itself is a tribute to lost colleagues and friends, as William Knocke, a top College of Engineering administrator, explains: “We owe it to them to continue pushing forward and not let that day be the defining aspect of what we’re about.”

Hokie Nation is moving on—united in its desire to commemorate the dead by living the school’s slogan: Invent the future.

“With every passing day, things get a little better for us,” assures College of Engineering Dean Richard Benson, who has managed a staff scattered among five buildings from a temporary, box-lined office for the past 10 months. In many ways, reflects Benson, tragedy has strengthened the school’s sense of community and purpose. “My ultimate goal is not to get back to where we were on April 16, but to go beyond,” he says. “We’re moving on but not forgetting.”

How Virginia Tech’s engineers salvaged the school year, promoted healing, and got people and programs back on track shows what can happen when uncommon generosity meets workaday resilience. “Everyone just came forward,” recalls Benson. “It was just extraordinary.”

Equally extraordinary are the lessons that emerged—on how to prepare for emergencies, identify students requiring mental health treatment or cope with excruciating trauma and grief. The wider engineering community might benefit from them, because if violence can strike Virginia Tech’s close-knit, sheltered campus in the Appalachian foothills, it can strike anywhere. As February’s eerily similar shooting at Northern Illinois University shows, we are all Hokies now.

The Longest Day

Date: Mon, 16 Apr 2007 09:26:24 -0400

From: Unirel@vt.edu

Subject: Shooting on campus.

To: Multiple recipients <LISTSERV@LISTSERV.VT.EDU>

A shooting incident occurred at West Amber Johnston earlier this morning. Police are on the scene and are investigating.

The university community is urged to be cautious and are asked to contact Virginia Tech Police if you observe anything suspicious or with information on the case. Contact Virginia Tech Police at 231-6411

Stay attuned to the www.vt.edu. We will post as soon as we have more information.

The morning of terror arrived on an unseasonably bitter wind, with snow in the forecast. The first hint of trouble, though few recognized it at the time, came in the form of a campus-wide E-mail at 9:26 a.m. that mentioned a “shooting incident.” The hasty writer had misspelled the name of the school’s largest dormitory, West Ambler Johnston, where the shooting occurred.

Knocke, head of the Charles E. Via, Jr. Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, returned to his office after discussing the alert with his staff. Glancing out his window, he saw a student crawling along the ground outside Norris Hall, home to the dean’s office as well as classrooms, specialized labs and professors’ studies.

“My first thought was that it was a fraternity hazing thing,” recalls Knocke. Then another student dashed over and dragged the crawler to safety. Knocke realized this was no frat stunt. He spent the next few hours moving throughout Patton Hall, trying to keep students, staff and faculty safe. Police sharpshooters burst in, wanting to reach the roof for a better angle on the shooter. Knocke had to tell them the building had no roof access. “I feel bad. I did a lot of yelling at people,” he says now. In fact, his leadership during the crisis won him Engineering News-Record’s 2007 Top 25 Newsmakers Award of Excellence.

Over in his second floor Norris Hall office, Ishwar Puri, head of the Engineering Science and Mechanics (ESM) department, was laboring over a National Science Foundation proposal to fund an undergraduate nanotechnology project when what sounded like “this jackhammer” broke his concentration. The time: 9:42 a.m. A few moments later, a secretary ran in to say there was shooting down the hall. Meanwhile, the gunman had chained shut the building’s three exits, preventing escape or rescue.

Two colleagues, one a West Point graduate and combat veteran and the other a Holocaust survivor, recognized the deadly staccato of semiautomatic fire and began helping students and faculty to safety. The veteran, Michael Garvin, ran into the courtyard between Norris and Patton Hall and told students—several who had jumped from windows in Norris Hall—to get out of the open area. In room 204, someone peeked into the hall and saw the shooter. Instructor Liviu Librescu, 76, who was still shaky from a recent illness, braced himself against the wooden door. With dazzling presence of mind, the aeronautical engineer told his students, by then crouching in the back, to crank open the old windows, remove the screens, and jump. Twenty students made the leap and survived. Then-junior Josh Wargo, who was practiced at tae kwon do, even remembered to roll on hitting the ground to minimize injury. But one student apparently balked at the two-story jump. Cho sprayed the classroom door with bullets and gained entry, firing at the jumpers. He then killed the remaining student as well as Librescu, a Jew who had been interned in a labor camp after his native Romania aligned with Nazi Germany during World War II.

Date: Mon, 16 Apr 2007 09:50:07 -0400

From: Unirel@vt.edu

Subject: PLease stay put

To: Multiple recipients <LISTSERV@LISTSERV.VT.EDU>

A gunman is loose on campus. Stay in buildings until further notice. Stay away from all windows.

An act of valor similar to Librescu’s unfolded on the floor above. ESM professor Kevin Granata, one of the nation’s top researchers in biomechanics, had just seen the E-mail alert when a colleague crossed the hall to ask about the noise disturbing his class. Granata shepherded the professor and 20 students into his office, told them to keep the door locked and set out to investigate, along with veteran engineering professor Wally Grant. The gunman shot them both, killing Granata and wounding Grant, who has only recently returned to teaching. Department head Puri believes Granata, who was noted in particular for his work in understanding the effects of cerebral palsy on movement, “would have thought it was his duty” to protect students, even at the cost of his own life.

From his window, Puri could now see law enforcement officers swarming into the courtyard. He phoned a doctoral student due to take an exam later that morning and ordered him to stay home. Puri’s duties as department head include sounding a foghorn in emergencies because Norris Hall has no electronic alarm system. But that day he refrained, not wanting to goad the gunman.

By the time police shot the bolt off a ground-floor lab door and surged into the stairwell, the killer was firing his final shot. It had taken just 11 minutes to extinguish 30 bright lives along one corridor, five of them venerated educators and scholars. Another 17, including a veteran engineering professor, were wounded, while six suffered injuries when jumping to safety.

Cho’s first target—classroom 206, where beloved professor G.V. Loganathan taught Advanced Hydrology—took a particularly painful hit. Eight graduate students, about one fourth of those in the civil and environmental engineering department’s water resources program, and one undergraduate were killed along with Loganathan, considered one of Virginia Tech’s most outstanding and caring educators. Just 4 of 13 students survived, 2 of them as a result of being shielded by the bodies of their classmates. Two were seriously wounded.

Down in Puerto Rico at ASEE’s annual meeting of the Engineering Deans Institute, Virginia Tech engineering dean Richard Benson called his office during the first break. His assistant didn’t answer. She and many of the dean’s office staff were in a stairwell, where they discovered the gunman had chained the exit. The group escaped through an unlocked door in the basement. Benson next got no response from his wife, who also worked on campus. She had sought refuge in an interior office. When Benson went up to his room, he turned on CNN and saw the horror unfolding at home. Packing hurriedly, Benson started the long trip back to Blacksburg, arriving shortly before midnight.

Back on campus, the engineering faculty hustled to identify potential victims. What classes were scheduled for Norris Hall that morning? Who was enrolled? “Our first priority was to take stock of what transpired,” explains Puri. Word reached them that Librescu may have been shot. So did accounts of students leaping from high windows.

Clearly, nearby emergency rooms must be filling with victims, the instructors concluded. With laptops from the mechanical engineering department, they drew up a list of likely victims. Puri took the list and ran from the building, a strong wind causing his unbuttoned coat to flap like a cape. He drove through the eerily quiet campus, deserted except for the occasional news truck, and headed to Montgomery Regional Hospital, arriving alongside students and distraught families in search of friends or loved ones. While a physician checked Puri’s list against the hospital’s intake roster, the ESM department head fielded calls from colleagues in Italy, victims’ relatives, and anxious spouses. The latter included Granata’s wife. “Have you seen Kevin?” she asked. Puri’s heart sank as he realized his friend may have walked into the line of fire.

It took roughly 24 hours to learn who had died and who had survived. By then, Dean Benson was back, seated at a large conference table in Durham Hall and working elbow to elbow with assistant deans on the myriad problems of a traumatized campus. An early priority was effective communication. The information technology staff pared down the school’s Web site so worried families could access and share information more easily.

“It looked like a fraternity, without the beer,” recalls Benson of this temporary command post. Spouses, colleagues and friends brought in food. Proximity bred efficiency and provided emotional support. “We had each other to lean on,” notes Benson. Any organization dealing with a crisis needs such a gathering place, he feels. “In hindsight, I’d recommend it.”

Salvaging the School Year

Notes of sympathy and support poured into the school—from alumni, elementary school pupils in Chicago, engineering schools and the White House. When Josh Wargo belatedly checked his Facebook.com page, he was amazed to see hundreds of messages from well-wishers and friends. For administrators and instructors, the remaining weeks of the semester passed in a blur of stress and adrenaline. Duties ranged from painful—attending memorial services, consoling bereaved families and arranging for bodies to be shipped home—to merely tedious—reassembling Ph.D. committees, finding classroom space for more than 1,500 students who had used Norris Hall each week and reassigning courses taught by slain professors.

“Looking back on that time, I don’t know how I went on from one day to the next,” says Knocke. Faculty members and graduate students offered to teach extra classes, as did faculty from other schools, some volunteering to come at their own expense. A research project requiring specialized equipment found a new home at Johns Hopkins University while funding agencies extended filing deadlines.

Reconstructing grades proved a grim task. It meant scouring a deceased student’s desk to figure out what lab reports had been graded, or gaining access to a dead T.A.’s laptop to see what marks had yet to be turned in. A special civil engineering team scrutinized ungraded homework and lab reports. Students were allowed to forgo final exams and accept the grades they had already earned in the course or take pass-fail credit.

Victoria Boivin, then a freshman, took the pass-fail option for half her classes. Once school resumed, she says, coursework became secondary in importance to relationships. In the final weeks of the semester, she wanted “to make sure friends were OK before everyone left for the summer.” Seth Williamson, a second-semester junior who had been safe in his dorm room during the shootings, opted not to take finals, but was one of the few who continued to go to class until the school year ended. He felt “this was the least I could do” to honor Loganathan and slain graduate-student TA Jeremy Herbstritt, who had taught fluid mechanics.

Not every logistical problem could be solved. With Norris Hall shuttered for two months and its entrances guarded by police, many of ESM’s faculty and 105 graduate students lacked access to their labs, equipment, notes, data, books and years of results. Labs were cancelled, courses were truncated and space was tight, even though colleagues willingly shared offices.

Still, Benson decided that emotions were too raw for the College of Engineering to move back to Norris Hall. In December, the university announced that the building will never again be used for general classes. The wing where Cho killed 30 and wounded 17 will house a new Center for Peace Studies and Violence Prevention along with new labs and learning spaces for the Department of Engineering Science and Mechanics. The engineering school will occupy new space in Torgersen Hall vacated by some of the university’s information technology personnel. “If we’d reassembled in our former quarters, I’m convinced that people would have left,” Benson says. He notes that at Colombine High School near Denver, Colo., a “shockingly high” number of staffers left in the years following a 1999 shooting rampage.

Perhaps so, but Ishwar Puri elected to move his department back to Norris Hall, ESM’s home since 1958. The site is too prime, the specialized labs too valuable, and the alumni too distinguished for the building to be abandoned as an engineering center, he says. It saddens him that some colleagues won’t attend meetings in Norris Hall, now refurbished with white-painted halls, or even drop by.

“Does that one event tarnish us so greatly that all our previous accomplishments are meaningless?” he asks. Puri also has argued against installing memorials and reminders of the dead within Norris Hall: “We can’t work in an everyday aura of tragedy. We want a building that’s vibrant. We want to bring it back to life.” Some students agree: “It’s not the building that’s scary,” Wargo says. To Victoria Boivin, the fact that Cho happened to choose Norris Hall was just “a freak thing.”

Lasting Pain

The anguish over Norris Hall’s future is one of a number of subtle clues that Hokie Nation continues to wrestle with April 16 demons. Soon after the shootings, professional grief counselors arrived to help faculty and staff recognize the attention lapses, exaggerated emotions and other signs of distress in students—and themselves. Now, they form a permanent fixture with a formal name: the Office of Recovery and Support. In February, as the first anniversary approached, the counseling center began hosting a series of evening get-togethers for friends of the victims. Flyers urging students to sign up for the university’s new emergency text-message and cell-phone alert system adorn bulletin boards. “Folks are fragile,” notes the manager of a popular town watering hole.

Randy Dymond senses this fragility. “The psychological fallout is unbelievable,” says the associate professor of civil engineering, who is also director of the Center for Geospatial Information Technology. Soon after the shootings, Dymond hosted a series of potluck dinners for the civil engineering survivors, believing that “by sharing their tales and talking, they’ll see that life does go on.” He also coordinated a team to help with G. V. Loganathan’s undergraduate civil engineering course and taught one of two summer classes, remembering how, when he took time off after his father was diagnosed with terminal cancer, Loganathan had covered for him.

Photos of the victims, many the same age as his own son, beam from Dymond’s computer screen saver. They serve as a regular reminder of the need to be “more approachable, friendlier” to students, to smile and take time to banter before and after class—and be alert for tell-tale signs of trauma. “As human beings, we tend to get comfortable in our routines and perceptions,” explains Dymond. “Some people may be living through something different.”

Yet by many measures, this has been a banner year for the College of Engineering. Continuing on its rapid growth path, it saw a 20 percent hike in research funds. Ranking 11th in the National Science Foundation’s ranking of total research expenditures, it is also 4th in ASEE’s tally of full-time teaching faculty. Researchers scored breakthroughs in the use of bioluminescence to pinpoint tumors, in wearable computers, and in nanotechnology, and they’ve won competitions for unmanned vehicle design. On March 1, two Virginia Tech engineers, James Thorp and Arun Phadke, received the Franklin Institute’s Benjamin Franklin Medal in Electrical Engineering for their work in strengthening the power grid. Past Franklin medals, in various fields, have gone to such luminaries as Albert Einstein, Thomas Edison and Marie and Pierre Curie.

None of last September’s incoming graduate students pulled out as a result of April 16. “What I’ve seen has only convinced me to affirm that my decision to attend Virginia Tech is the right one,” one of them wrote to Knocke. Nor did the tragedy dampen enrollment: 70 more freshmen entered than the engineering college had anticipated—or had room for. Many students who chose other schools wrote to explain that the shootings had nothing to do with their decision. A record number of students are slated to earn engineering Ph.D.s this year.

“I was almost offended when people asked me if I was going back to Tech,” recalls mechanical engineering major Victoria Boivin, who couldn’t imagine not returning for sophomore year. One of the older students who had been an inspiration to women engineers, chemical engineering senior Maxine Turner, was among those killed, Boivin recalls. The Alpha Omega Epsilon sorority created a scholarship fund in Turner’s name. Seth Williamson, who also came back, recalls that the murders were “in the back of most people’s minds” at first, but that now, a sense of normalcy has returned.

Kevin Sterne personifies how Virginia Tech’s sense of community has strengthened. He is the former Eagle Scout who was shot twice on April 16 and staunched his hemorrhaging right leg with an electrical cord. A photo of him being carried to safety, bloodied and partially clad, became the massacre’s iconic image. Although wounded students were allowed to take extended leave, he was among those who returned to finish the year. When Sterne graduated with a degree in electrical engineering, cheers erupted from the audience as he advanced across the stage with the aid of a crutch to collect his diploma. Rather than head for Colorado in September to pursue a master’s degree, he chose to stay at Virginia Tech—a decision that helped land him an honored place at President Bush’s State of the Union address.

Such public tributes have aided the healing process, many at Virginia Tech contend. Randy Dymond, for example, marveled at how the spirits of eight survivors were lifted when Louisiana State University invited them to watch Virginia Tech’s football showdown with LSU. The outpouring of sympathy—and money—from alumni and strangers comforted countless souls.

The first anniversary will again draw the nation’s attention. A day of remembrance is planned, but the impact of April 16 already extends well beyond candlelight tributes and beyond Virginia Tech. It shows in the beefed-up emergency plans and text-message alerts that prompted Northern Illinois University’s rapid response when a gunman opened fire on a crowded lecture hall this February. It appears in the lobbying by Virginia Tech officials, students, and victims’ parents to close Virginia’s gun-buying loopholes and boost student mental-health programs to help avert future acts of senseless violence.

“No one can understand why this happened,” observes Dymond. “All we can do is remember and honor and push hard to remind our politicians that something should come of this.”

With the school’s recovery comes time for new reflection and commitment. “Tragedy made us realize the jewels that we had,” concludes Puri. “Service to students is now indelibly etched in blood in our department and the university.”

Mary Lord is a freelance writer based in Washington, D.C.

Category: Features